This article originally appeared in the October 1985 issue of SPIN.

For too long, a lot of excuses have been made for David Crosby. Sadly, that may be part of his problem. This special report doesn’t offer, or accept, any excuses.

More from Spin:

- David Crosby and the Late-Career Resurgence That No One Saw Coming

- David Crosby’s 10 Best Songs

- Neil Young on David Crosby: ‘I Remember The Best Times’

Marin County, California. The rich farmland rolls past, dotted by flocks of grazing goats and sheep and clapboard barns with their red paint peeling in the sun. An occasional tractor lumbers by on a blacktop road, the driver lazily waving hello from the cab.

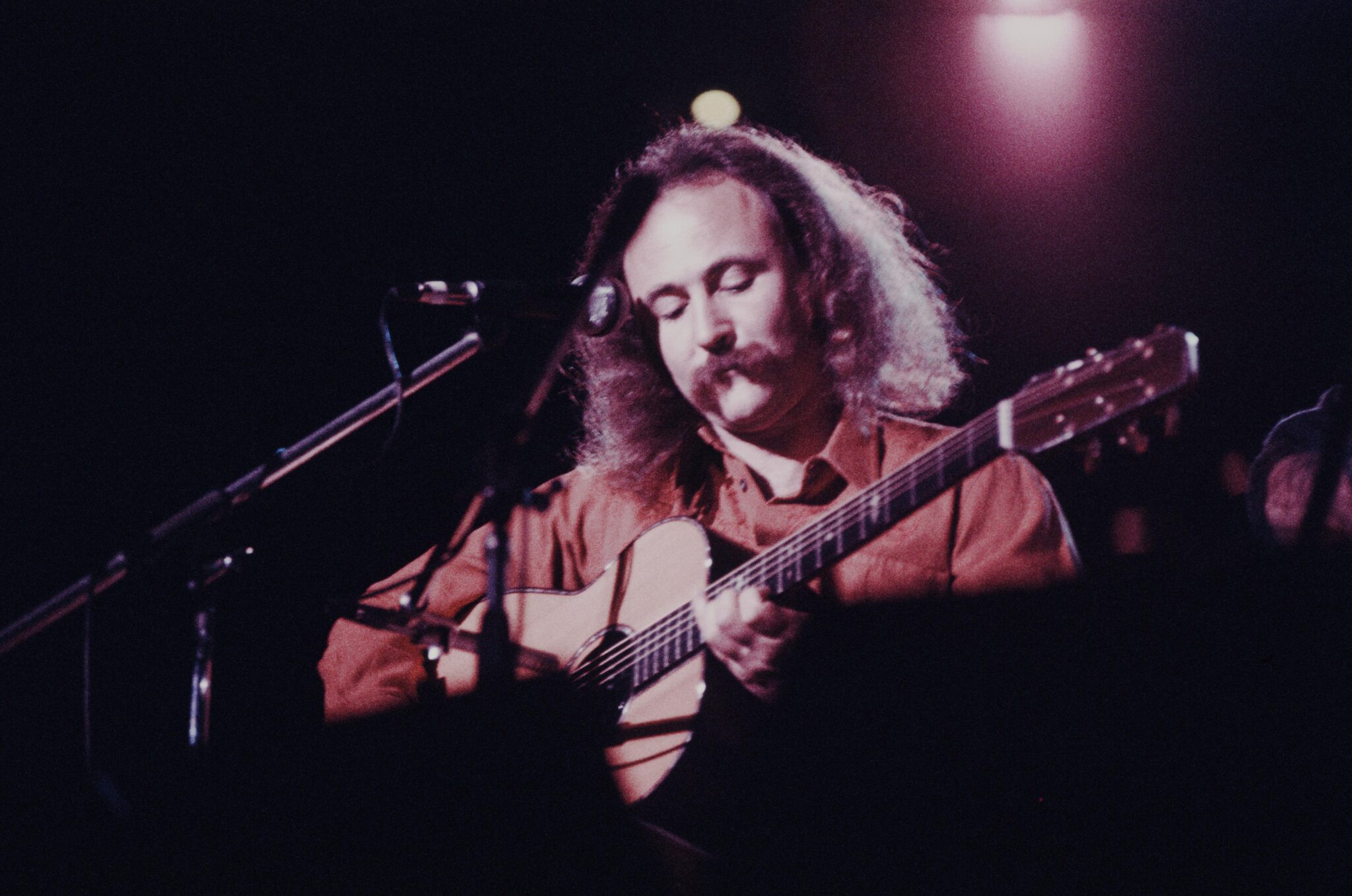

About 15 miles outside Novato, California, in a particularly deserted spot, a gravel driveway bends off a backwoods road, leading to a gray house fortified with security cameras. It’s here, after a week of cryptic phone calls and suddenly canceled appointments, that I’m supposed to meet with David Crosby. The former member of the Byrds, and partner of Stills, Nash, and Young, who’s been called an “American Beatle” for writing such classics as “Long Time Gone” and “Guinnevere,” has arranged the meeting through his business manager, Jack Casanova. Yet repeated knocks on the front door bring no response. Though several cars are parked in the driveway, my shouts go unanswered. Nothing stirs. Suddenly a cat jumps onto a window ledge and peers through the Levolor blinds.

The silence lasts about 20 minutes. Then a burly, shirtless man with a hairy, sagging paunch appears at the front door. “Jack Casanova,” he says, and he invites me into his house. “David will be out in a few minutes. Sit down. I’ll put the VCR on. Enjoy yourself.” And as he disappears into the rear of the house, a porno film flickers onto the screen.

I wait. Instead of following the nude acrobatics on TV, I watch the tabby edge across the living room. Carefully sliding past Oriental vases, low-slung leather sofas, and other modern furnishings, it curls up contentedly in a corner and drifts off to sleep.

I’m not as comfortable. Tired of waiting, I leave the house and walk around outside. Thirty more minutes go by. As the sun sets, a Mercedes pulls into the driveway, and a well-dressed couple enters the garage. When I go back inside, the house is deeply quiet. An emaciated, barely dressed woman eventually strolls into the kitchen, grabs a bag of potato chips, and vanishes behind a sliding door. She giggles childishly as the door slams shut.

David has been arrested four times on various drug and weapons charges since 1982. Invariably escaping long-term incarceration, he’s retained an aura of ’60s lawlessness, a romantic bad-boy image that boosts his value on the revival circuit.

But David’s continued freedom is always in doubt. He was busted in a Dallas rock club in 1982 for possession of a quarter gram of cocaine and a loaded .45. His 1983 conviction on these charges was later overturned on a legal technicality, but last June a Texas appeals court reinstated the original verdict. A five-year jail sentence now hangs over his head while his case is again appealed, but attorneys’ fees, coupled with years of expensive drug use and repayment of a $3 million debt to the IRS, have plunged David into murky financial waters. A group of shadowy financial backers supports him and during the recent CSN tour, they carefully monitored all interviews to promote the notion that the “new” David is drug-free. Yet, on several occasions he has barely escaped torching himself to death while freebasing.

“When David set fire to his hotel rooms, I paid the bills out of my pocket. I just wanted to keep everything going,” says Michael Gaiman, president of the Cannibal Agency, who booked a Crosby tour in 1984. “I didn’t want David to get arrested. People would say half-kiddingly that he’s down from 7 grams to 2 grams a day, but he and his girlfriend Jan Dance were going to hell arm in arm. I’ll never forget, after he torched his suite in the Vista International [in New York], Jan was sitting there shaking, the wall was scorched, the sheets burnt, and David looked like he hadn’t bathed in weeks. He said, ‘You gotta help me, man, you gotta help me, man.'”

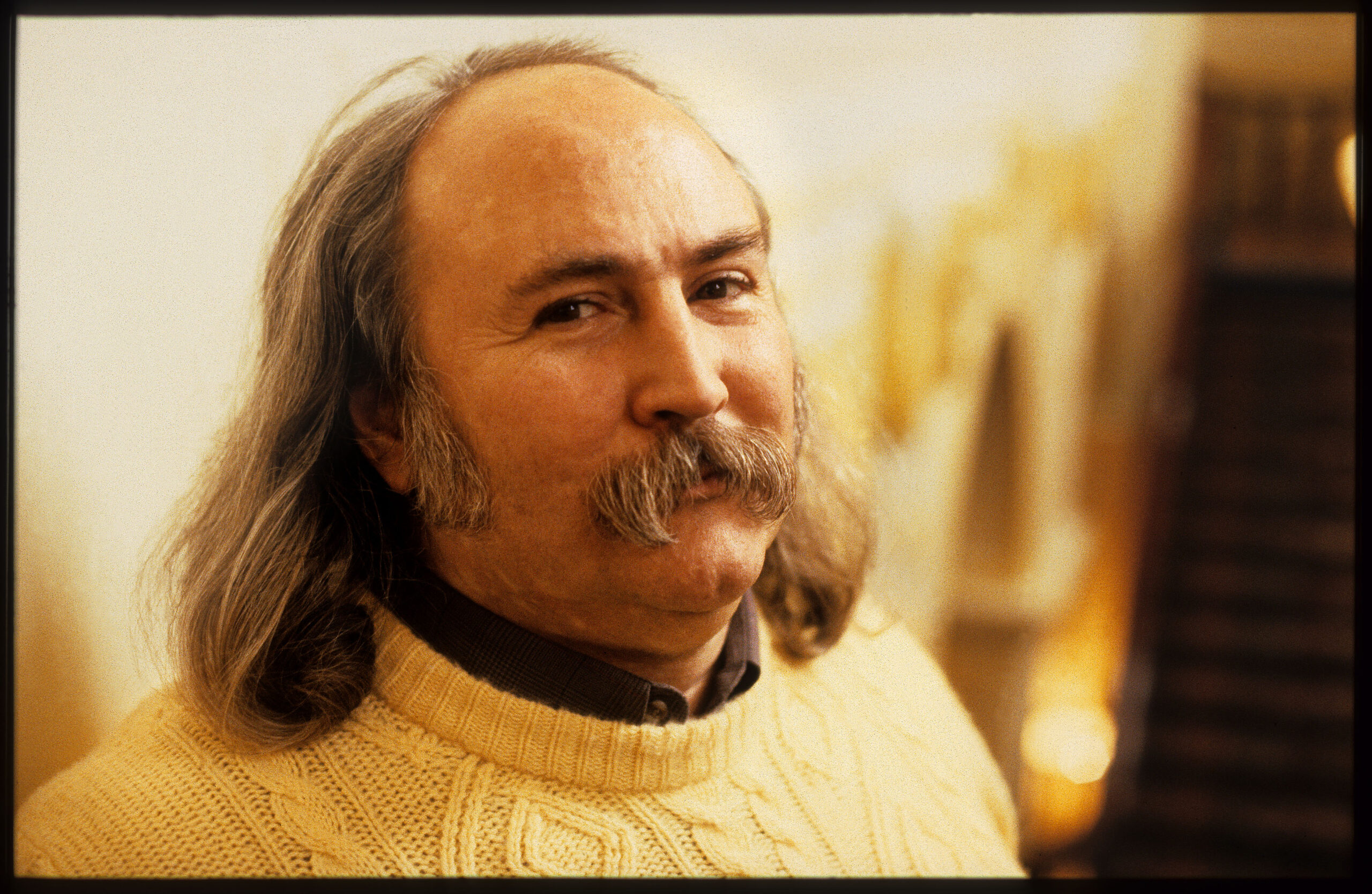

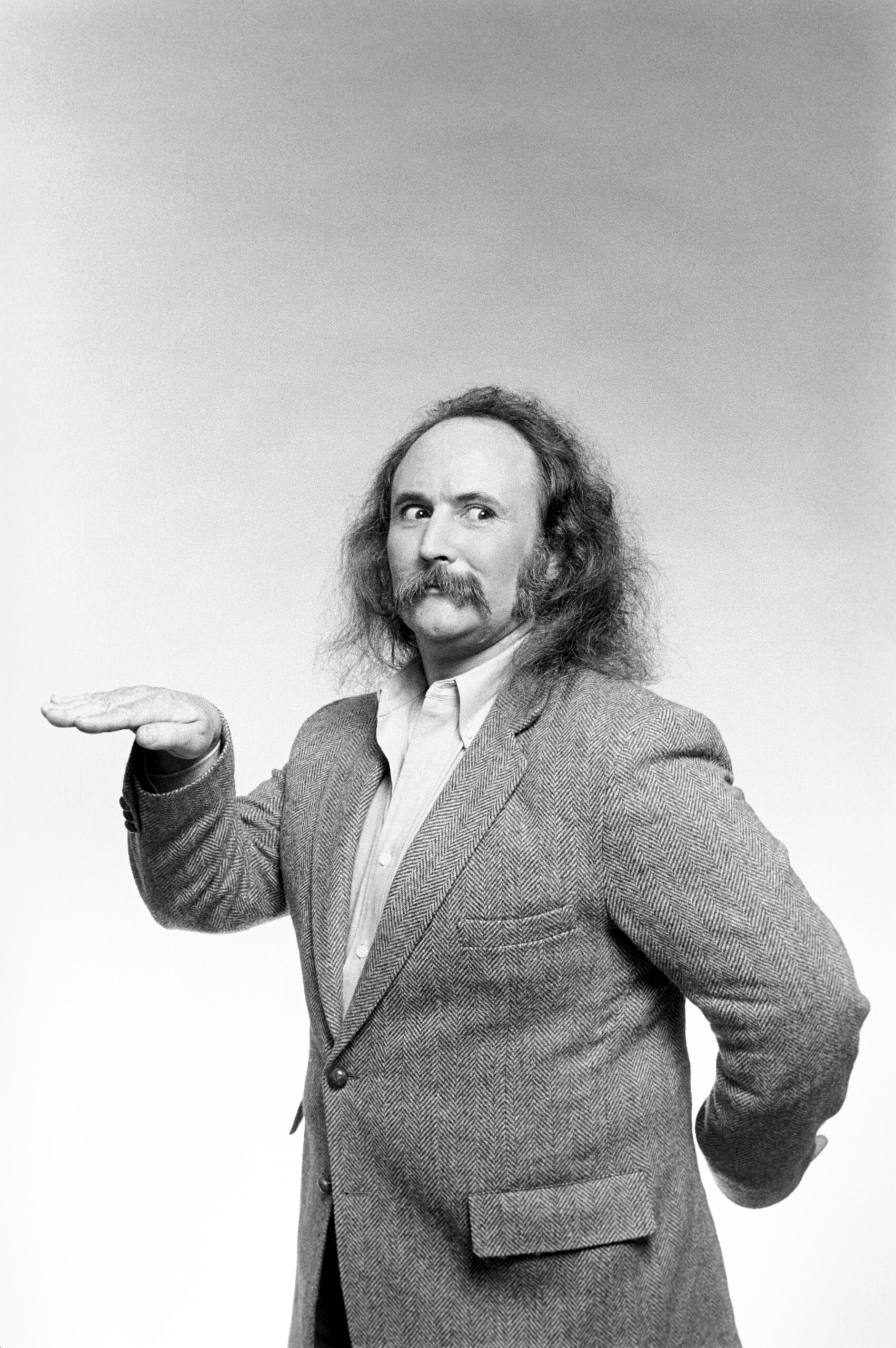

A door bangs shut and a disheveled, unshaven figure staggers into the living room. David has finally appeared. His stomach is bloated; his thinning, frizzy hair leaps wildly into the air. A few of his front teeth are missing, his pants are tattered, and his red plaid shirt has a gaping hole. The most frightening thing is his pale, swollen face, riddled with thick, white scales, deep and encrusted blotches that aren’t healing. Looking at him is painful. A 14-year addiction to heroin and cocaine has caused David to resemble a diseased Bowery bum. The spiritual leader of the Woodstock Nation is now a vision of decay.

David slumps into a chair. “Getting sad and missing people who aren’t there anymore is the worst,” he says. “Do you know that ‘Each man is an island’ thing? That’s no joke, man, everybody is. I’m alone a lot. I don’t handle it well at all. I’m not good at it. I’ve lost a lot of friends, musicians. I’ve lost an old lady too, Chris, Christine Hinton, she was killed in an auto accident. I wrote a number of things that refer to her—’Guinnevere,’ ‘Where Will I Be’ . . . I miss so many people — Cass Elliot, Jimi Hendrix, Janis. Lowell George was a dear friend of mine. There’s an enormous list of folks . . .

“I’m sad, very sad, but I don’t have the urge to go over the edge. The French have a phrase, raison d’etre, a reason for being, and I have several strong reasons for living. There’s my music—look at what they gave me to work with [a reference to his strained voice]. My daughter, sailing, all the adventures I haven’t been on yet, all the music I haven’t written or sung yet. Almost nothing makes people happy, man, there’s very little in this world that really makes people happy, and I can. I can pull off that magic trick by myself sometimes. I love doing that. I love it when we sing ‘Teach Your Children’ and get 20,000 people singing it. People are touched and moved by that. It changes them, it changes how they feel. They’re less alone.”

Joel Bernstein, David’s long-time friend, earlier had said he doubted that David could still perform that magic. “The drug’s become very big in his vision. It is so important to him, getting it, processing it . . . I think he’s done more coke than anyone in this country. He’d deny that and say music was more important. But the drug was definitely affecting his music. . . . He was abusing his nostrils so much, damaging them so much. I’ve done harmonies with David, and I’ve seen how the drugs affect his performance. The real tragedy of David is the fact that his musical potential has been so impeded.”

Drugs have reduced David’s voice to a whisper. Every word is a strain on his throat. Where there was once hope, there is now the vocal equivalent of coarse sandpaper, a dull, flat rasp.

“I quit completely,” says the 44-year-old Crosby as he grabs for a bag of Pepperidge Farm cookies.

“You gave up coke?”

“Yeah!”

“Heroin?”

“Yeah!”

“You were doing coke and heroin?”

“I’d rather not talk about that. Coke I’ll admit to. And I did quit, completely. It changed things considerably. I’m not into it at all on the level I once was. I don’t . . . for the most part I don’t do it. I’ll agree with them [Bernstein, Graham Nash, Jackson Browne, and others who came to David’s house in 1983 to persuade him to seek help]. I was too much into it.”

Looking pained, David stares vacantly ahead. Disregarding the laughter in another room, he resumes, “I do good work, I want to work with those guys [Stephen Stills and Graham Nash]. I love them. . . . Drugs wouldn’t hurt my working with them now. Things have changed.”

Suddenly, a note of exasperation creeps into his voice. Looking beseechingly at me, he cries out, “Do we have to talk about drugs? Can you believe it, five years for less than a gram. I won’t get out of that state alive. I’ll die in one of those jails. . . . I don’t want to talk about drugs. It’s been used against me so many times. I just want to talk about my music.”

David’s eyes close; his head drifts into a slow nod. One eye barely opens when I ask him to describe how the Byrds broke up. He mumbles a few words and quickly falls back into a stupor.

I prod him a number of times. He comes to and without a word rises and stumbles to the door separating the two wings of the house. He pauses there for a moment, smiles wanly, then disappears. And I’m left sitting there, stunned.

Death and ruptured friendships have made David a lonely, wrenchingly sad figure. Tragic or premature losses dog him. His mother died of cancer. Christine Hinton, the 21-year-old woman he was passionately in love with, died in a violent 1969 car crash. Since the late ’60s, he’s been estranged from his father, Floyd Crosby, the Academy Award-winning cinematographer who worked on High Noon and Tabu. Embroiled in a child-support battle with former girlfriend Debbie Donovan, he rarely sees his 10-year-old daughter Donovan Ann. And while David was once surrounded by such artists as Grace Slick, Elvis Costello, and Jackson Browne, his closest friends—Bernstein, Roger McGuinn, road manager Armando Hurley, Paul Kantner, and Jaws 2 screenwriter Carl Gottlieb—have either severed ties or don’t want to talk about him. As CSN tour publicist Bob Gibson admits, “David’s friends have thrown in the towel. It could be that jail is the best place for him.”

Alienated from his friends, David has drifted in and out of a netherworld where only the next fix is important. Desperate for drugs, he has sold musical instruments to raise cash for cocaine. And while this belies his oft-repeated claim that music is his primary concern, his so-called raison d’etre, freebasing is a sickness that has often rendered him helpless.

David’s friends have repeatedly tried to admit him to hospitals, lent him money, and brought drug counselors to his Mill Valley, California, house. But David has disappointed them by rejecting their efforts with contempt or by agreeing to seek help and then fleeing from clinics.

“We’ve tried to do everything short of imprisoning him, but David looks down on almost all of his friends. He thinks he’s the king of the world,” said Jefferson Airplane cofounder Paul Kantner in 1984. Suggesting that people shouldn’t feel sorry for David, Kantner continued, “If you take a thoroughbred horse, pamper and feed him all the fat grains and wonderful milks all day, pretty soon he’ll be a big fat horse who can’t run . . . and the same with musicians. If you put them in mansions, feed them steaks, you’re going to have some big fat guy à la David Crosby pushing shit into his arm and doing nothing but dying. I’m sad he’s put himself in the position he’s in. But he’s been an asshole even to his friends. Now no one accepts him, and he doesn’t want to be around us because we’ll tell him, ‘David, please stop.’ I hate to say it, but the boy’s a dead man.”

“David’s whole life has the earmarks of Belushi’s death,” says Armando Hurley, David’s confidant for 12 years.

Before John Belushi died alone at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, there was a battle for his soul. While friends tried to help him, agents and producers had more self-serving agendas for the comedian—and to make sure he delivered, they kept Belushi’s coke supply lines open. A similar fight rages around David. On one side there are people like Graham Nash, who is tirelessly devoted to David, both emotionally and financially. David’s Dan Aykroyd, Nash has patiently shrugged off David’s frequent outbursts (“You’re not my conscience” is one of David’s favorite lines), rescued him from jail cells, and sheltered him in his Hawaii home. Though a CSN tour is worth considerably more than either a Nash or Stills solo (booking agent Gaiman says that together they can demand $75,000 a night, compared with $15,000 to $25,000 for only one of them), Nash seems to genuinely care about David, whom he calls “Boy David.”

But there are other forces competing for control of David’s life—the drug dealers, financiers, and music people who see David only as an investment and have little or no interest in his health, and the Marin County motorcycle gangs and underworld types who supply him with coke and heroin.

And while David’s financial backers want to keep him alive so he’ll pay back old debts or generate income, they can hardly choke off his drug supply. If they took a strong stand, David could either find new “friends,” circumvent their safeguards, or simply stop performing for them. Besides, under the influence, he’s far more gentle and accommodating.

“The only people David deals with outside of Graham are a fucking mess. All they want from his whole trip are drugs or some kickback,” says Joe Healy, road manager for David’s 1984 solo tour. “Before the tour began, this guy I didn’t know comes into the house I’m renting, and while I’m on crutches he jumps me and kicks my ass. We go through the whole tour, and this backer comes up and says, ‘I need a recording session from you guys.’ I look up and it’s the mother who jumped me. . . . You don’t want to know his name. It’s just too much of a stone to upturn. He threatened to kill me. He’s a sicko.

“David owes this guy about $250,000. After the CSN tour this summer, David could pay this guy off and walk away with some of his possessions. But right now David’s not strong enough to walk away. You have to understand, David’s sick, and he’s in the hands of the wrong people.”

When a bank threatened to foreclose on David’s house, a man named Jack Casanova came up with the money to help him. Pudgier than Lou Costello and equally squat, the nearly bald, bearded Casanova also gave David the money to record a yet-unreleased album and has helped him pay other debts. A self-described “dabbler” in real estate and other business ventures, Casanova says he has known David for 10 years and is a great fan.

Casanova ignored several requests to be interviewed until this past July, then blamed CSN management (the Crosslight Agency) for not relaying my messages to him. He describes himself as David’s right-hand man, but remains a mysterious figure.

“Jack seemed to know nothing about rock ‘n’ roll,” says Michael Gaiman. “[On the ’84 tour] he never asked about gross potentials, contracts, percentages, nothing. I’d explain the dates, the grosses to him, and you would expect some input. But I didn’t get anything from him . . . I asked around about Jack and a pal of his who carried around this silver case and always seemed tooted up, and it became clear that they hadn’t been in the music business before. So I had to wonder how they got to be working with David.”

While under Casanova’s care on the ’84 tour, David left a trail of hotel wreckage behind him. Unable to control a propane torch—the basic tool of freebasing—he burned his room in New York’s Vista International, damaged furnishings at the Yankee Pedlar in Torrington, Connecticut, and burned the interior of his tour bus.

After these incidents, David resembled a character out of a B horror movie. Covered with blood and spittle, he’d vacantly glare at people. Angry hotel keepers wanted him arrested. Casanova indifferently shrugs off these episodes.

“David does owe me some money, because he owed a lot of money to the [CSN] partnership, and he had overspent on tours,” Casanova says. “He had some tax liens, and he had to take care of those [David has paid $3 million to the IRS over the past 10 years]. I put together some investors, who bought David’s house. David has an option on his house—it’s no longer in his name. But he still lives there, and he makes the payments. He still owes some money [to the IRS], he just paid off a $74,000 lien, and that took care of a great deal of his taxes.”

What about the stories that the people around David are violent and shadowy?

“That’s ridiculous. There’s no violence in any of these people or me. And there’s no record of any violence whatsoever. If there’s some hearsay story about something, I have no idea what it might be.

“I get paid, I get paid quite well. David has given me part interest in the masters on some of his new tunes. There’s no debt to me other than what he promised to pay me and was not able to because of previous debts. David owes me money because I’ve not been paid what he’s promised to pay me for aiding him, consulting him, helping with his house, and so on.”

His voice alternating between anger and frustration, Casanova says he saved David’s relationship with CSN. “I talked to Graham [before the 1984 CSN tour], and he said, ‘Look, I love David, but I’m never going to play with him ’til he’s clean. And Stephen’s scared.’ On the [1983] European tour, and the tour before that, David had musicians out in the street looking for drugs for him. He spent a great deal of money, far more than Stills and Nash, which he had to recoup. In fact, at the beginning of the last tour he still owed the partnership $56,000, which he repaid. I told Graham that now that his house had been saved David seemed to have enough financing, that he could do basically what he wanted to do on the tour, that he wouldn’t be sending people out and endangering the whole band, that he cut his drug intake down to between a third and a half of what it was. Everyone was kind of negative about David.”

Casanova claims the CSN management company’s two bosses, Bill Siddons and Peter Goldin, betrayed David. “Listen, we seldom ever saw them on the tour. They’re not on the [’85] tour. I think they’re doing a shitty job. Why? They’re not paying enough attention to the management of David. I would like them to take more of an interest in who David Crosby is. They’ve told a lot of people that David doesn’t look as good now as before he went into the hospital. They’ve made decisions without David and me. They’re not going to be David’s managers very long, that’s what it amounts to.

“It’s really easy to see who’s interested in money and who’s interested in the act first and the money second. David had some heavy, heavy legal fees to pay, and his expenses aren’t small. David was short of money, especially at the beginning of the [1984] tour—he was broke. [Siddons and Goldin] assumed that every time David wanted a thousand dollars he was going to buy some dope. And they wanted to play lecturer to him. He had to put out as much as $20,000 to $25,000 at one time to have his attorneys continue in Texas, because he was behind in paying. And they all sat down with me one night and they were telling me how much they loved David. So when David had to send all this money to Texas to keep his attorneys working, not one of them said, ‘Look, I’ll put up a couple thousand bucks. I stand to make another $50,000, I’ll put up $2,000.’ Not a goddamned penny. Who was at that meeting? Siddons, Goldin—all the honchos, all the well-paid folks.”

Vaguely remembering that meeting, Siddons says, “Our track record speaks very clearly. We have always shown deep concern for David and what we feel is best for David. We were never asked to participate in paying David’s legal expenses, and we’ve never asked him to help pay ours. We’ve always looked out for David’s interests and will continue to do so.”

Yet Armando Hurley, who became so disgusted with the “slimebags” surrounding David that he left the CSN entourage in 1984, insists, “I couldn’t handle any of these guys anymore. I got into this terrible argument with Siddons over drugs. I can’t talk about the specifics, but our ethics are a lot different. Bill Siddons is only interested in Bill Siddons. I think he thinks David is a pain in the ass.”

Bethel, New York, August 17, 1969—The phone rings at midnight in Michael Lang’s production office backstage at Woodstock. An assistant takes the call and, crestfallen, relays the news to festival organizer Lang.

“They’re not coming. They’re stuck at the fucking airport in New York.”

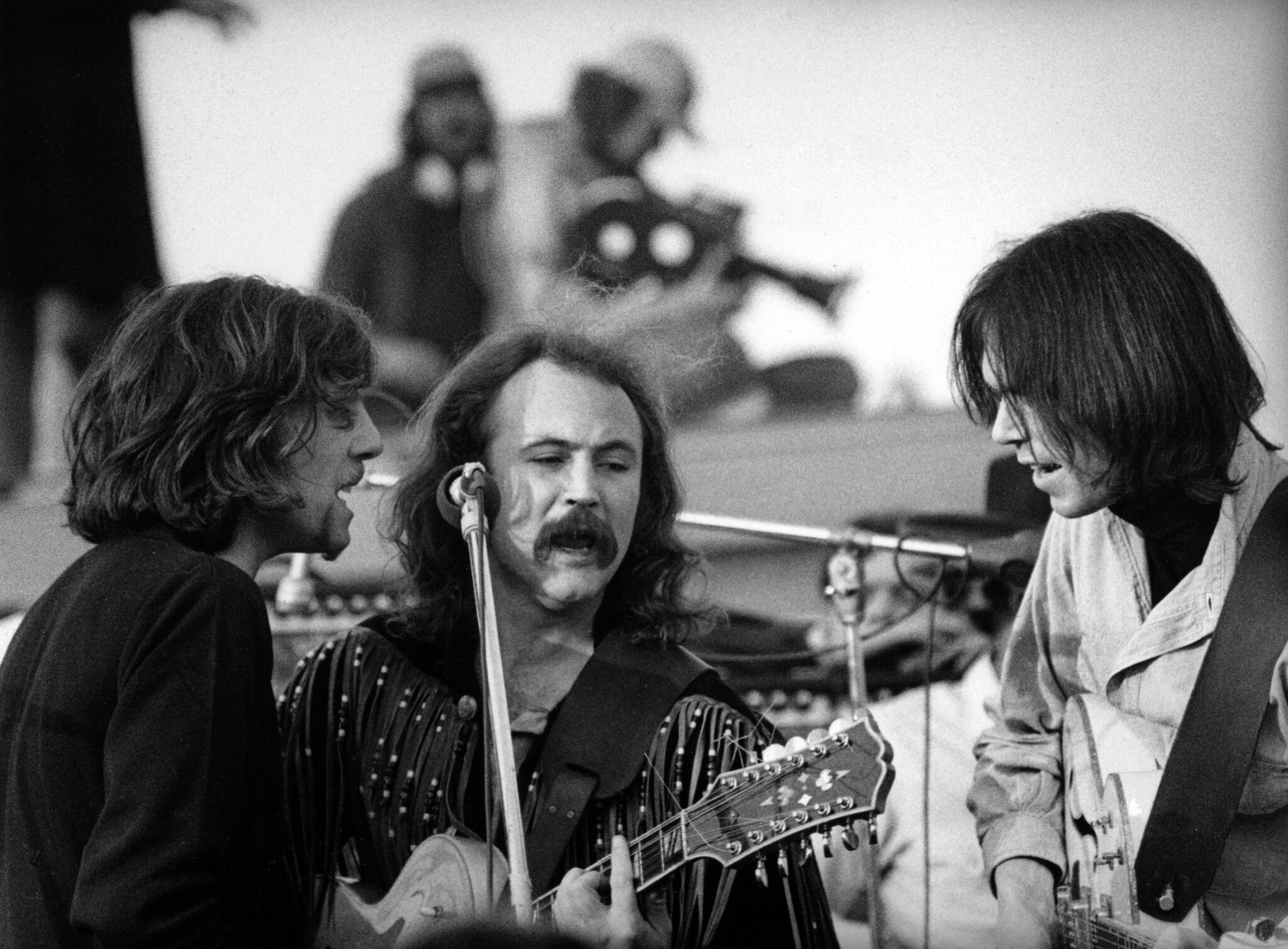

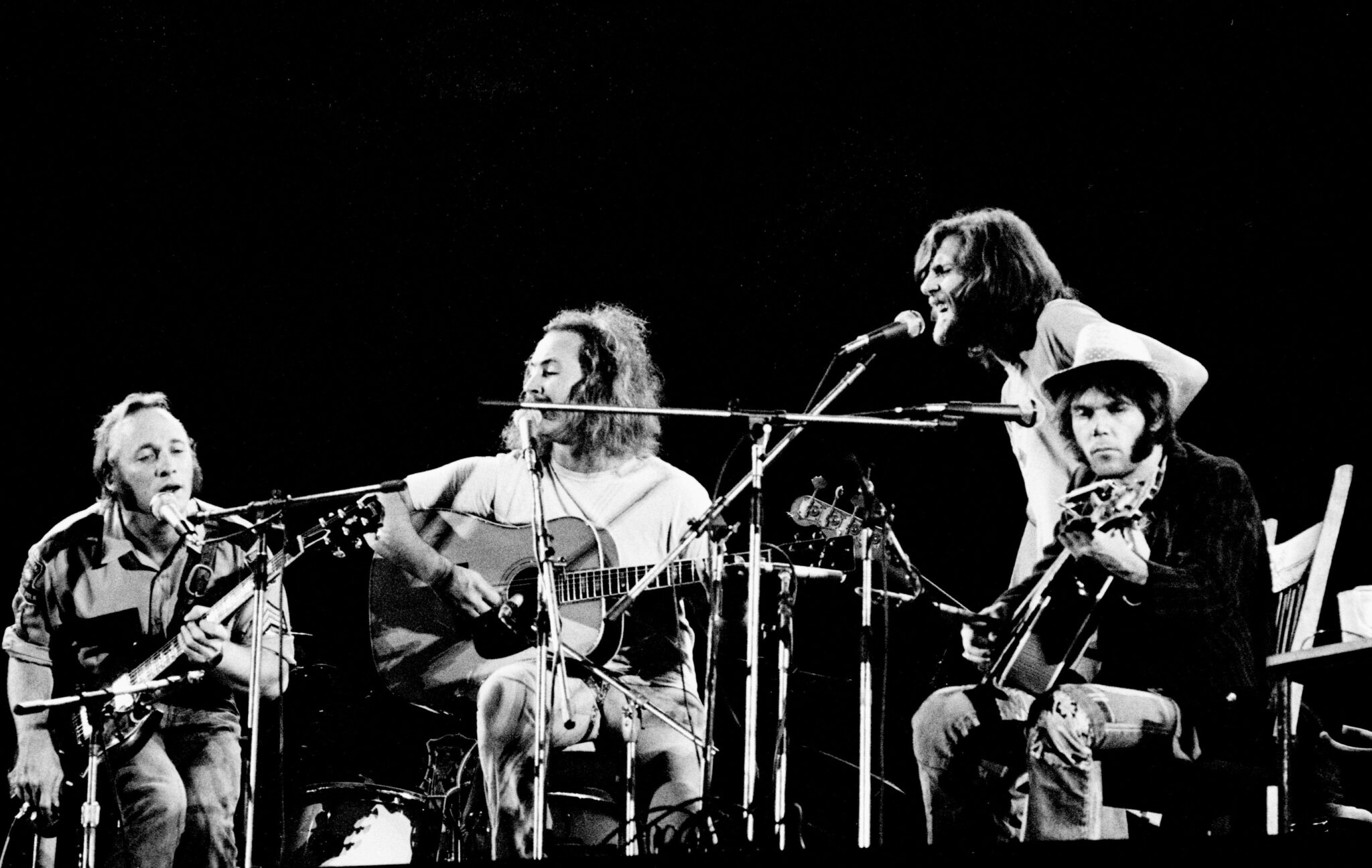

The Aquarian Age is dawning without CSN&Y. While over 400,000 faithful listen to Joan Baez, the Who, and Jefferson Airplane during a driving rainstorm, David and the other members of the group can’t get transportation to the upstate New York festival. Finally convincing an airline representative to rent them two planes, the group defies the weather and arrives backstage at Woodstock around 3 AM.

They quickly strut out front. Stills exclaims to the mud-soaked, LSD-imbibing crowd, “You gotta be the strongest bunch of people I ever saw.” Then CSN&Y begin what will become among the most famous first bars of a rock anthem, the tripping guitar intro to “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.”

The applause is deafening.

CSN&Y are now the heralded leaders of the Woodstock Generation.

And David Crosby is the group’s driving force.

Though arrogant and volatile, he had been a leader before with the Byrds. There had been trouble, ugly spats with the other Byrds. But he moved on, became Joni Mitchell’s producer, her guiding spirit, and even her lover.

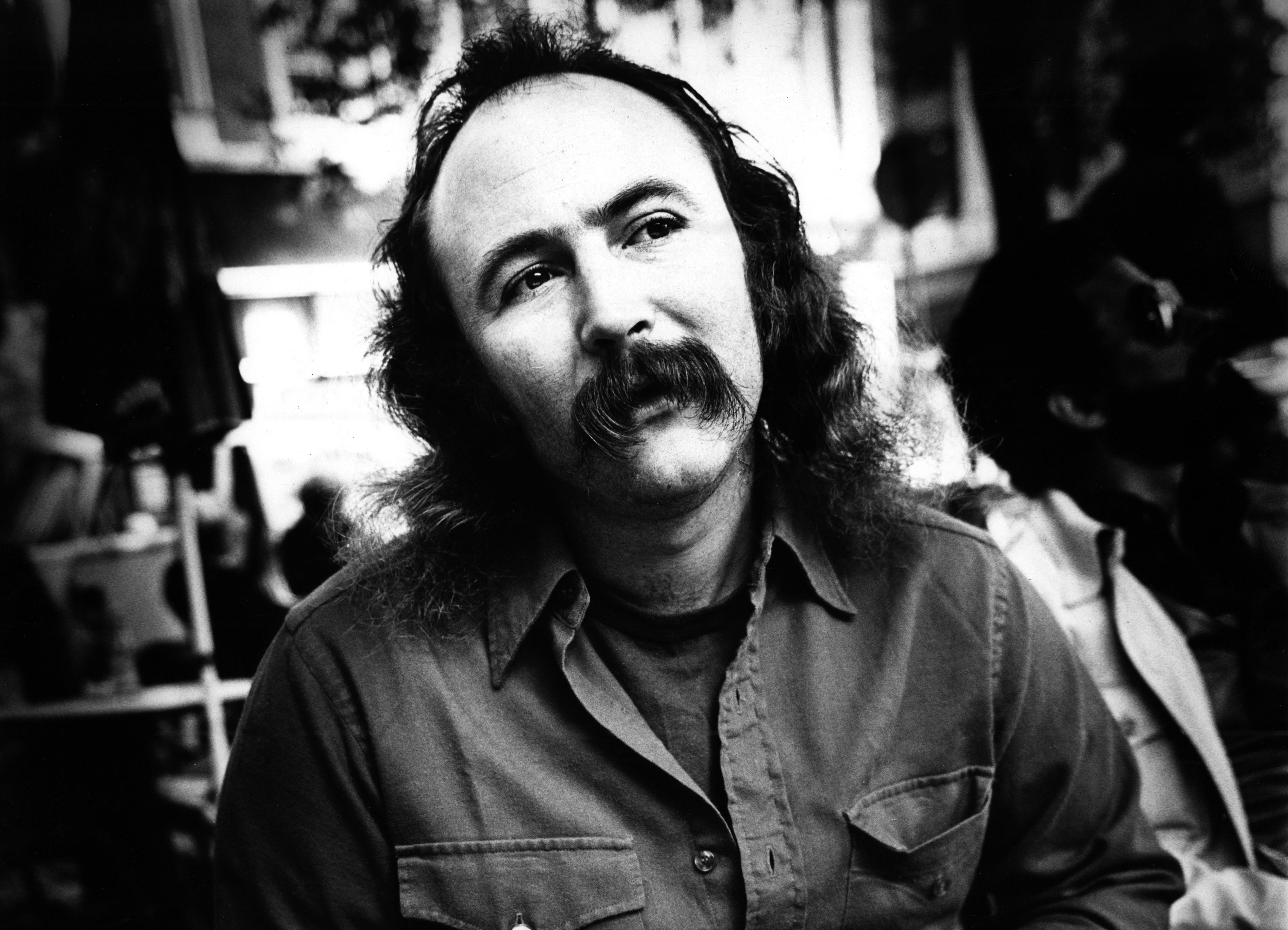

In those halcyon days, David only smoked marijuana and dreamed of owning a sailboat. Friends saw him as an innocent yet committed musician. When Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, he was shocked into writing “Long Time Gone.” To John Sebastian, Grace Slick, and Eric Clapton, David was an inspiration, the long-mustached, flowing-red-haired figure they adoringly called “Yosemite Sam.”

Winning such esteem was a struggle for David. Both as an adolescent and as an early-’60s rocker, he faced innumerable obstacles. And the torments on the way to Woodstock, the estrangement from his family, and personality clashes with fellow band members left their scars.

His childhood was especially tormented. The son of a celebrated cinematographer who socialized with Roger Corman, John Huston, and other Hollywood icons, David felt the pressure to succeed—or to “match up.” Shattered by his parents’ divorce and unable to conform in school, he became the quintessential ’50s juvenile delinquent. As a teenager in Santa Barbara, he broke into cars and houses and, most troubling of all to his father, played folk music at beatnik coffeehouses.

“Floyd basically turned his back on David. He wasn’t interested in his son’s music, and that hurt David,” says Chris Hillman, one of David’s friends from the Byrds. “How could David like himself? He came from a real unstable family.”

Floyd Crosby still thinks his son made grave mistakes. Now 85 and living quietly in Ojai, California, where his main pastime is gardening, Floyd says, “David had success, but he got caught up with drugs. This meant a lot of trouble. I talked to him about drugs, but it didn’t do any good. I haven’t seen him in three years.”

In 1960, hoping to please his father, David enrolled at the Pasadena Playhouse acting school. Compelled to “kiss ass” and to “fake” his true feelings, the outspoken, quick-tempered David soon dropped out to play blues guitar at the Unicorn in L.A. After getting his Hollywood girlfriend, Cindy, pregnant, he fled to New York, learned a new playing style from folk singer Fred Neil, and hitchhiked around the country. He lived with Dino Valenti, later of the Youngbloods, on a houseboat in Sausalito, but finally returned to L.A. in 1963. At a Troubadour club hoot, Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark were impressed with David’s “fresh, energetic voice” and asked him to join their group, the Jet Set, which later became the Byrds.

In 1964, the Byrds recorded Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” and took off. But as their stature grew, David began competing with McGuinn for control of the group.

“There was always a rub between me and David. He had to be on top, and this rivalry often turned ugly in the studio,” sighs McGuinn, recalling the time drummer Michael Clarke was angered by David’s “shit” and punched him in the face. “The tension hurt the Byrds terribly. We’d be searching for material and fights would break out. They got physical, and David was often at the center of them.”

David was experimenting with cocaine by the mid-’60s, and emblematic of this interest, he collaborated with McGuinn to write “Eight Miles High.” But hostilities peaked in 1967, when the Byrds refused to record David’s song about a menage à trois, “Triad.” McGuinn said the lyrics were “immoral.” Angered, David complained that the Byrds were “canaries” who stunted his musical growth.

“David thought I was censoring him, that I was mindless and unhip because I was into Eastern religions,” says McGuinn. “But ‘Triad’ was simply a bad song, and David had just become too tough to deal with. There was bad blood between us, so Chris Hillman and I asked him to leave. David said, ‘Come on, guys, we make good music together.’ But I told him, ‘We make good music without you.'”

David was already hanging out with Stephen Stills. The Byrds gave him a $50,000 settlement, and with it he bought a boat, the Mayan. Inspired by idyllic trips on the Mayan, David teamed with Stills and Paul Kantner to write the revolutionary anthem “Wooden Ships.” It was the beginning of the historic group that would become CSN&Y.

In 1968, David fell in love with a wispy, blonde-haired California girl named Christine Hinton. Luxuriating on beaches or swimming naked in Monkee Peter Tork’s Laurel Canyon pool, the couple epitomized the Aquarian Age. They enjoyed life, and in this beatific spirit, David sang harmonies with Stills and Nash at Joni Mitchell’s house. “We knew we’d locked onto something so special,” David told writer Dave Zimmer.

The world soon felt the same way. In 1969, their debut album, Crosby, Stills, and Nash, featured “Long Time Gone,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” and “Marrakesh Express.” It sold 2 million copies. The album had a lilting, soothing quality that was a stark contrast to the frenetic politics of the era. CSN was likened to the Beatles by the American counterculture, and Jimi Hendrix raved, “These guys are groovy . . . western sky music. All delicate and ding-ding-ding-ding.”

The euphoria persisted all the way to Woodstock. Together with Neil Young, who joined the group shortly before the festival, the group made their second live appearance as Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young at Max Yasgur’s farm, and the “music and arts fair” cemented their reputation as love children.

Still enraptured by Christine Hinton and hailed as the group’s driving spirit, David was excited by life. Happier than he’d ever been, he didn’t use “peace and love” as mere buzzwords. To him, the phrase had real meaning as he stood poised to lead the Movement to an even higher consciousness.

As my wait for David grinds on, I sit in that eerie Novato house—30 minutes have passed . . . 40 . . . 50 . . . —wondering what happened to him—and the revolution. During that apocalyptic era, protestors marched to his music, echoed his calls for freedom. David and the forces of rebellion were intertwined. Then and now. For his weakened condition, which has forced him into a back room to revive, is symbolic of the lost Revolution.

David reappears, mysteriously rubbing the edge of a large brass bowl with a wooden cylinder. His slow, circular strokes make the bowl reverberate, and a shrill, piercing hum fills the room.

“That’s nice, eh,” says David. “It’s Tibetan. It drives the bad Mojo out of the room.” His eyes are bleary, the sound is annoying. “Anyone who’s bad has to leave. I haven’t been to Tibet, but I’ve seen pictures of the people’s faces. They’re all happy, they’re still free, they haven’t been conquered. That’s why I’d like to get there.”

Woodstock was also an uplifting experience, he cheerfully exclaims. “That was good, man, real good. We didn’t realize at the time what was going on quite as much as we did later. But it was amazing for us, because we were just starling out. Everybody in the entire music business that we respected was standing all around us, looking to see what we were going to be. And we were nervous. Everybody was there, the Who, Hendrix, everybody, the Airplane . . . it was quite something. It was good, man.

“We [CSN&Y] were all good writers. We had this incredibly wide palette to paint the albums from. Those days were the best, man. We were doing work that we thought was absolutely the best of our lives, and it probably was. We were tight buddies. I love Stills, and Nash has been my best friend for many, many, many years, and still is. He’s one of the best men I know in the world. We played for the right reasons, because we loved it. Music was our whole life, the main joy in our life. It gave us purpose . . .”

David’s voice trails off mournfully, and he moves to the window to stare at a lone farmworker on a distant hillside. He’s trying to hide the tears glistening in his eyes. But like the shadows creeping over the surrounding fields, David is enveloped by darkness, the darkness of a past suddenly clouded by tragedy.

On September 30, 1969, only a month after his Woodstock “high,” David was frolicking with Nash, Christine Hinton, and other friends by the pool in back of his Marin County home. Chris rolled a few joints. Carefree and high, she gathered up their four cats and put them in David’s ’64 VW bus and drove off to the veterinarian. On the way, one of the cats suddenly jumped onto her lap. The VW swerved into the path of an oncoming school bus. On impact, Chris flew through the windshield. She died a short time later in a hospital emergency room.

“I don’t think David ever recovered from that accident,” says Armando Hurley. “It was one of those ideal love affairs; he thought she was perfect for him. She was his utopia. The loss was very heavy. It hung over him like a ball and chain in his life.”

The inspiration for “Guinnevere,” Christine represented David’s non-drugged, creative side. He eulogized her in “Laughing” (“And I thought I’d seen someone / Who seemed at last / To know the truth / I was mistaken / It was only a child laughing in the sun / Ah! In the sun”), and “Deja Vu.” David made the arrangements for Christine’s cremation. Afterwards, he carried a deep guilt over her death.

David is standing forlornly by the window. “‘Deja Vu’ was my song, and I’m proud of it. This was a different experience for me. After Chris died I’d go to the studio and just sit on the floor and cry.”

David was in a stupor for months. He didn’t regain his sense of purpose until May 1970, when four Kent State students were killed during a campus demonstration. Calling that incident a nightmare, he speaks with new clarity, a passion that’s reminiscent of the old David.

“I remember handing Neil [Young] Life magazine, and he looked at the pictures of the girl kneeling over the guy dead on the pavement, looking up with that ‘Why?’ expression on her face. I saw the shock of it hit him. I handed him his guitar and helped him write ‘Ohio.’ I got him on a plane, took him to L.A., and we recorded that night. By 1 o’clock in the morning we passed the tape to Ahmet Ertegun, the president of Atlantic Records, and got on a plane to New York. It was out in three days. And we point the finger, we could say [starts to sing] ‘Tin soldiers and Nixon coming / We’re finally on our own / This morning I hear the drumming / Four dead in Ohio / Gotta get down to it / Soldiers are cutting us down . . .’

“It was a bitch, and to be able to put that song out, man, right away [his voice rises again], and have it stand for something, have people stop us in the street and say, ‘Man, right-fucking-on.’ That was exciting. It was good stuff.”

But this peak couldn’t be sustained, and an atmosphere of mistrust and acrimony enveloped Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. The main battle raged between Stills and Nash, who bitterly vied for the affections of Rita Coolidge. Stills fought with Young for the greater share of lead vocals. Young finally settled the issue by going solo. The group flew apart. David left to rejoin the Byrds. CSN&Y re-grouped at other times during the late ’70s, but muses David sadly, “When we got big, music was sacrificed on the altar of ego again and again and again.”

While his eyes remain pained, David fervently insists, “Music is magic, man. There hasn’t been a major magic on the planet since the caveman danced around his fire going ‘ugga-bugga, ugga-bugga.’ Music is what people do when they feel good. It’s a magic, it’s an elevating force in our lives, in our consciousness. It makes us not alone.

“Issues were crystallizing that polarized the country in the ’60s and made everyone think they had to stand up and be counted. Music was a unifying force. ‘Long Time Gone’ seemed to mean a lot to people. ‘Almost Cut My Hair’ seemed to mean a lot. So did ‘Teach Your Children.’

“Apathy overtook everything,” says David, “There are big divisive issues that are tearing the country up. The same people are still running the country, and they’re getting ready to get us into another war. They’ll sacrifice 100,000 people in the blink of an eye. You can smell the new war a-coming.

“It’s sort of a guerrilla warfare that I play, where I try to spot one of those moments when you can affect everything hugely by just one small act, one human being standing up and sticking up for the right thing. I look for those moments. I’m praying I’ll come across one.”

His voice cracks with emotion. Standing up again, he clenches his fists. He then stares at me, and in a barely audible tone, says beseechingly, “I don’t harm anybody, I don’t steal, lie, or cheat, or mess with other people’s old ladies or anything. I’ve tried really hard to be a decent human being. All I do is go around and make people feel good—that’s my whole life’s work, to make people happy. I try really hard to be a positive force.”

But, like that of many flower children, David’s revolutionary ardor cooled in the 1970s. He continued to mourn Christine’s death and retreated to a more private world. He became romantically involved with a woman Hurley describes as “warm, exciting, with a great body.” Charmed by David’s wit and intelligence, she began doing a lot of cocaine. Their relationship flourished until she decided to go straight.

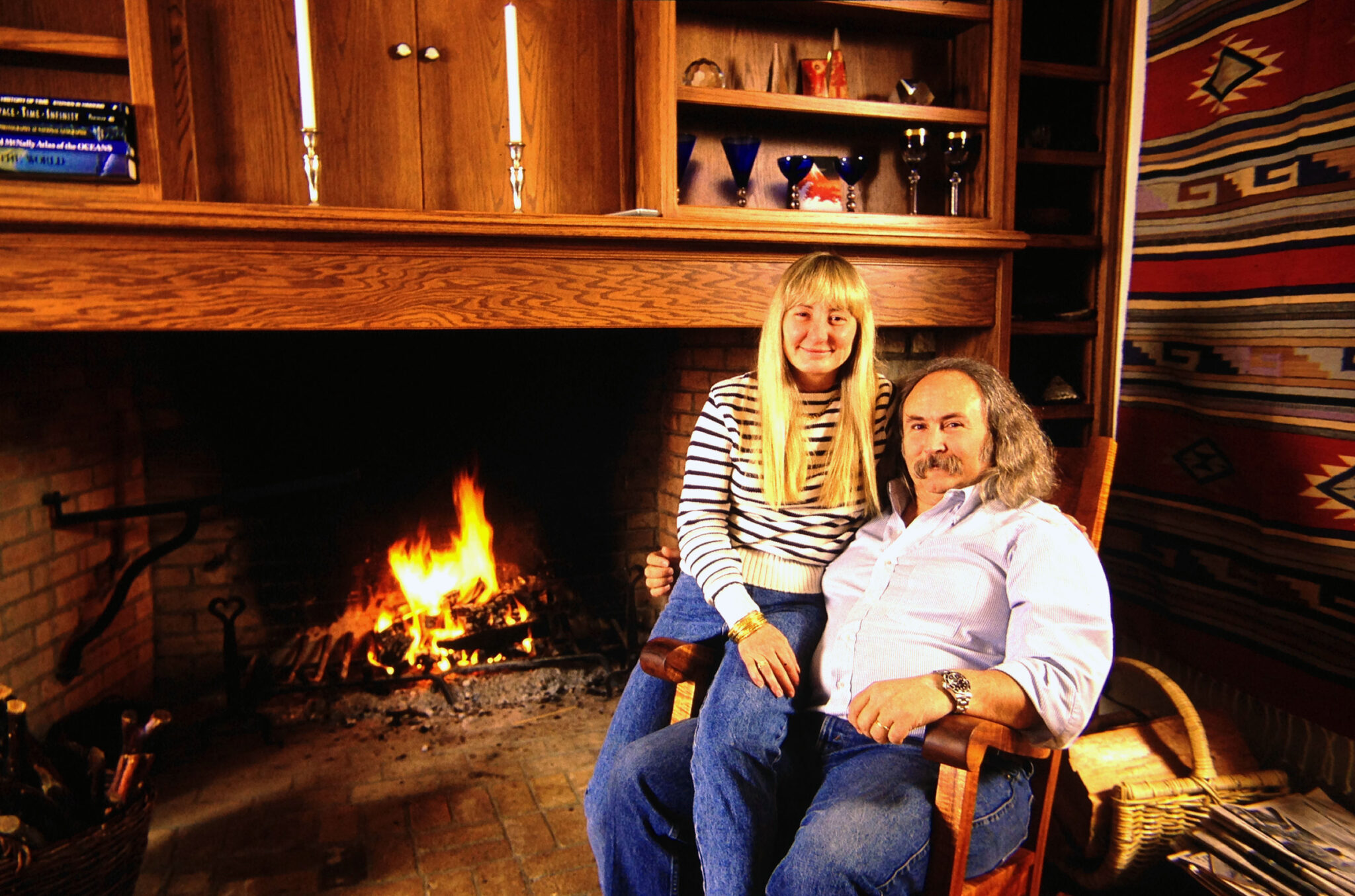

Then David met Jan Dance.

The quintessential Florida beach girl, Jan Dance made heads spin. She was all flowing sandy hair, a carefree smile, girlish innocence, and wholesome good looks. Petite and always laughing, she bounced instead of walked. All the boys agreed: she was perfectly molded for tie-dyed T-shirts.

David met Jan in a North Miami recording studio in 1979, where she was the PR director. He was immediately smitten. He invited her out on his boat. They saw more and more of each other. All was idyllic. With her next to him, he didn’t have to think of Christine. Jan was a rainbow of different colors.

As he had done with several other women, David turned Jan on to cocaine. They began freebasing together, and she soon became his partner in pathos. “Jan’s not the villain here at all, she’s a victim. David got her going,” sighs Armando Hurley. “When I first met her she was so vibrant, so filled with tomorrow. But when David wanted something from women he got it, and now you could put Jan in with the Biafrans. She’s so emaciated, she’s death warmed over.”

The word was spreading quickly. In L.A. and in Marin, David’s closest friends heard that he had a drug problem. In early 1981, the story travelled like a brushfire that while on tour David had twice fallen unconscious after freebasing.

Some members of the music community doubted David would survive the year. Cynics wagered among themselves on when he’d finally do himself in.

Others wanted to help him, but what could be done? One night in 1981, Kantner, Grace Slick, Jackson Browne, Joel Bernstein, and a few others finally decided to act. They confronted David at his house and implored him to enter a drug rehabilitation program. David broke down, tearfully confessing that he had “a severe problem,” and agreed to seek help.

“It was a very emotional meeting; David went through a real catharsis,” recalls Joel Bernstein. “We had this room ready for him at a private hospital, and when he realized that we weren’t talking about his quitting eventually, but that we wanted him to do it right now, he broke down again.

“He eventually said he’d go to the hospital, but insisted on spending one last night in his house. After we resolved this, David went back to his room and started freebasing! It seemed as if he just wanted to stall us, that he was only interested in getting to his bedroom. Nash got very angry at him. I think he realized that David was acting in front of us, that he was playing the role of someone needing help. But he wanted to stop the conversation so he could freebase.

“Well, the next day Jackson brought him down to the Scripps Institute in La Jolla and got him admitted. But one day later David walked.”

Having angered and alienated his friends, David found himself increasingly alone. Now only Jan was by his side, and she had her own cocaine problem. David began hanging out with street people in Mill Valley. Ever afraid of getting busted or hurt, David became acutely paranoid.

“David has always loved guns, but as the drugs intensified, his fear of dying or being murdered was amplified,” says Hurley. “The John Lennon thing really shook David up. He thought it was a gross insult to humanity, and the whole idea of being killed by a fan freaked him right out. So he always had a gun with him.

“Then, when Belushi died, it really shocked him. Belushi died in bungalow three at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, and that’s where David always stayed! That thoroughly unnerved him.”

As David drove to an anti-nuclear rally on March 28, 1982, cocaine and a .45 revolver were concealed by his side. Nodding off enroute, he crashed into a divider on the San Diego Freeway. When police searched his car he was arrested for possessing methaqualone, cocaine paraphernalia, and the gun as well as for driving recklessly. He was allowed to plead guilty to the driving violation, while the other charges were dropped, and was sentenced to three years probation, fined $751, and ordered to enroll in a drug program. However, this latter stipulation was never enforced. Said one court official, “The guy simply got a slap on the wrist.”

A few weeks later, David was again in trouble. Big trouble.

Desperate for money, even if it meant playing in sleazy bars, on April 13, 1982, David turned up at Cardi’s, a now defunct rock club in the northeast section of Dallas notorious for the numerous shootings and stabbings that had taken place in or around it. That didn’t deter David. He was ready for all sorts of action.

Around midnight, two cops responded to a fight that had broken out in the parking lot outside the club. One cop entered Cardi’s and went backstage. He saw David holding a propane torch in one hand and a pipe in the other. As the policeman approached, David flung aside a green bag that contained coke and a loaded .45 and screamed, “Don’t do this to me, don’t do this to me!”

Hiring two of Dallas’s most celebrated defense attorneys, Jay Ethington and Jerry Banks, David made emotional appeals in court. “Jail is no joke,” he told Judge Patrick McDowell. “Handcuffs are no joke. It’s real serious stuff. It’s been very lonely. I spent a lot of nights lying there thinking about it. Those bars are very real. It certainly frightened me. I don’t want to do anything ever again, ever, that puts me in jeopardy. I want to feel proud of myself and stand for something again.”

But Dallas DA Knox Fitzpatrick wasn’t moved. Fitzpatrick is said to have the mind set of Clint Eastwood. The Texas lawman hardly looks like a law-and-order zealot. He is short and bulging in the middle. But Knox Fitzpatrick is a fit hunter. According to local newsman Steve McGonigle, “Knox thinks David is a dirtball. It’s bothered him that Crosby has gotten off so many times, and that he took this condescending attitude in court. He even fell asleep during the proceedings. So Knox has been dogged. In a sense, it’s become his case, his own personal vendetta.”

While David’s defense team contended that the search was illegal and moved for a dismissal of the case, Fitzpatrick relentlessly plodded ahead. He repeatedly drew attention to the evidence. Cold and dispassionate, he wanted David to do hard time, five years, in a state prison.

On June 3, 1983, Knox Fitzpatrick finally won. David was found guilty. But the legality of the search was disputed in Texas courts and David was freed on bond during the appeal. He told me, “For a thumbnail’s worth of pipe residue they sentenced me to five years. I guess they wanted to make an example of me. I’m scared, man.”

Despite his fears, David continued to freebase on his ’84 solo tour. In October of that year, David was arrested again for recklessly driving his motorcycle in the Marin County town of Ross. Police found in his possession heroin, cocaine, marijuana, a rubber hose tourniquet, a spoon, a torch, a pipe with coke residue, two daggers, a knife, white powder residue on two of the knives, and other narcotics paraphernalia. He was booked on weapon and drug charges. But since the legality of the search was “doubtful,” according to assistant DA Peter Evans, David was only prosecuted for reckless driving. David pleaded guilty to the driving charge (on two previous occasions he had been arrested or cited for a revoked license) and received three years probation and a $1,325 fine.

In Texas, Knox Fitzpatrick heard of David’s rearrest. He intensified his campaign to get David put away. Another hearing was held before Judge McDowell last December, and David was ordered into the drug rehabilitation program at the Fair Oaks Hospital in Summit, New Jersey.

The Fair Oaks Hospital sits at the crest of a gentle hill, surrounded by expansive lawns and rows of manicured trees. Cottages dot the grounds, and while the private, $800-a-day institution, one of the finest treatment centers in the U.S., has locked facilities for psychiatric patients, the quiet retreat looks more like a country club than a hospital.

David entered the hospital last January, and immediately refused to take part in any of the therapy sessions. He repeatedly begged Casanova to take him back to California. According to his counselor, Dr. Stephen Pittel, David would belligerently reject the staff’s overtures, then sob uncontrollably for help, then turn hostile again. He suffered from several illnesses, including edema (his ankles were swollen to four times their normal size), apnea (a condition where breathing stops for 20 to 30 seconds during sleep), and dental abcesses. “He was in tremendous agony,” says Pittel.

During the fifth week of confinement David began to participate in the program. He met with other drug abusers and talked about how addiction had ruined his life. He’d cry grievously during these traumatic sessions. He began composing music for the first time in three years, organized a hospital band, and asked for permission to bring in a synthesizer. The request was denied, but David continued to cooperate with the doctors. Hospital staffers believed David had “turned a corner.” He acted like a man transformed, strolling happily on Fair Oaks’ lawns.

On Sunday, February 24, during one of these walks, a car driven by an unidentified old girlfriend of David’s pulled up to the hospital, and he jumped in. He wasn’t seen for the next 26 hours—not until the New York police arrested him near Greenwich Village for possessing cocaine.

Unable to post a $10,000 bond, David was held at the Tombs and on Riker’s Island. Eventually, he was assigned an attorney from the public defender’s office, but he remained in jail for four days. He appeared at hearings wearing torn and badly stained clothes and barely spoke. From Texas, Knox Fitzpatrick dispatched two deputies to bring David back for having again violated his bond. David meekly submitted to Fitzpatrick’s demands for his extradition.

David was returned to Texas for another hearing on March 8. Dr. Stephen Pittel testified that David had been addicted to heroin and cocaine. Fitzpatrick demanded the revocation of his bail, while both defense attorneys pleaded to have him sent back to Fair Oaks. Judge McDowell, however, denied bond and sent David to the Dallas county jail.

On March 7, David was given a set of white coveralls and locked up in the “tank” that housed seven other inmates. He was made a trustee in the medical ward. For a week he swept and mopped floors in the infirmary and assisted guards in the cafeteria. He was granted other privileges, including the freedom to walk around a dayroom and to eat in the general dining room.

Yet the guards soon had trouble with him. On March 15, David was warned about eating food off the cafeteria carts as he served the other inmates. The following day he missed work and was again reprimanded. Complaining about not feeling well, he came late to work the next four days. David was stripped of his privileges and put in a more restrictive setting.

Confined for most of the day to a 40-square-foot cell, David spent the next month in virtual isolation. He constantly telephoned Casanova and lawyer David Vogelstein and pleaded with them to get him out. “[Jail] was worse than the hospital,” says Casanova. “It scared the shit out of him. He tried to get hold of me every day. He was afraid he’d never get out. He’d just plead with me and say, ‘Jack, you gotta get me out of here, please, please, man. I’ve been good, I did everything people told me to do. I took off for a little while, I know that was wrong. Please, get me out of here. I’m going crazy, I’m going to kill myself.'”

Except for lawyers Etherington and Banks and five people from the Dallas area, David received no visitors. Graham Nash, Stills, CSN management, his father, and even Casanova stayed away. Until he was released on May 1, David battled with drug withdrawal and incarceration alone.

Philadelphia, July 13, 1985—It is an emotional benediction. Joan Baez, the Mother Teresa of the ’60s counterculture, moves onto the Live Aid stage and dramatically proclaims to the crowd, “Welcome, children of the ’80s, this is your Woodstock.” As she sings “Amazing grace / How sweet the sound . . .” Baez seems to be trying to evoke ghosts of that rain-soaked, three-day conclave. But that’s a long time gone, and Live Aid isn’t “Woodstock II.” Too much has changed in America, in the music industry, and especially in David Crosby to justify such a comparison. In 1969, skinny-dipping hippies were taking LSD and chanting obscenities at Nixon, while at JFK Stadium short-haired preppies were waving the Stars and Stripes. Back then rock raged against the Establishment; today it’s a multibillion-dollar enterprise, a cornerstone of the American mainstream.

CSN has interrupted their troubled cross-country tour to appear at Live Aid. Initially, no one knew if there would even be a tour, since David was still in jail. Worried promoters called Bill Siddons to ask about David’s release, and Siddons could only fend them off with, “The lawyers are working on it.” Attorneys were also rumored to be working for Stills, who, reportedly tired of David’s drug problems, had allegedly filed legal papers to dissolve the group.

Nash remained more of a friend. Once David was released from jail, he spent a few weeks relaxing at Nash’s Hawaii home, returning to his Marin County haunts just before the trio regrouped in L.A. to rehearse for the tour. While CSN publicity people restricted David’s public appearances to create a new drug-free image for him, the old David was in evidence when the tour opened in Sacramento on June 28.

David Barton, a reviewer for the Sacramento Bee, told me David’s eyes were glazed onstage and that he seemed “very detached.” Barton called the show “pathetic.” “His voice was very weak, and he looked pale,” said Barton. “But the most depressing thing of all was David’s only comment to the audience. He told the crowd to hang on to loved ones, because ‘you don’t know how long you’ll have them.’ It was clear he was referring to Christine Hinton.”

Live Aid is a welcome break from the tensions of the tour. Graham Nash and Stephen Stills mingle with old friends in a “hospitality” area and watch other performers on a TV monitor outside their van. They show no ill effects from the early-morning flight and seem to be genuinely enjoying themselves.

Siddons had barred me from seeing Nash a few months earlier in L.A., saying, “It upsets Graham too much to talk about David; I don’t want his time in the studio to be affected.” As I approach Nash and tell him of Siddons’s ban, Siddons walks up and denies it. “I’m a big boy, I can handle myself,” says Nash. He invites me into the van to talk about “losing his friend” David.

“The prison term shocked him,” says Nash. “I think he fears the jaws of the wolf. But I haven’t seen it scare him enough. It’s terrible for me. I rarely see my friend. I don’t have the same rapport with him that I used to have. David likes to get high, he’s a sick man.

“I’m amazed that he’s still alive,” Nash says. “He’ll eventually die—it’s only a question of when. He won’t want to hear that. He’ll read that and despise me for a while. I’ve armored myself, but it’s heartbreaking.”

As Nash speaks, David remains closeted in a backstage van. Newly hired bodyguard “Smokey” Wendell (reporters are told that he’s a road manager) stands watch by the door. Except for CSN management people and an unidentified, tall, foxy-looking Oriental woman, no one gets past Wendell, who in 1980 was hired to keep John Belushi “clean” (at $1,000 a week). The solidly-built Wendell had previously been hired by David’s camp in the early ’80s, yet couldn’t keep drugs away from him, according to Armando Hurley. But now Wendell seems to have matters under control. When reporters ask to interview David, they are brusquely told, “NO way, David’s burned out.”

David stays in the van until CSN is summoned to a holding area directly behind the stage. As he prepares to go on, I can see that his face is covered with makeup. Yet the scars from his staph sores are still visible. Onstage, David Crosby, the counterculture’s “Yosemite Sam,” is barely able to stand upright. He is more evocative of Altamont’s savagery than of “Teach Your Children.” His stringy, thinning hair and bloated stomach are kept from the TV audience. There are closeups of Nash and Stills. But throughout CSN’s three songs, David is ignored.

After the performance, CSN is interviewed by MTV’s Alan Hunter, and here the trio is one happy family, talking about their tour and a still unfinished album that is scheduled to be released next April.

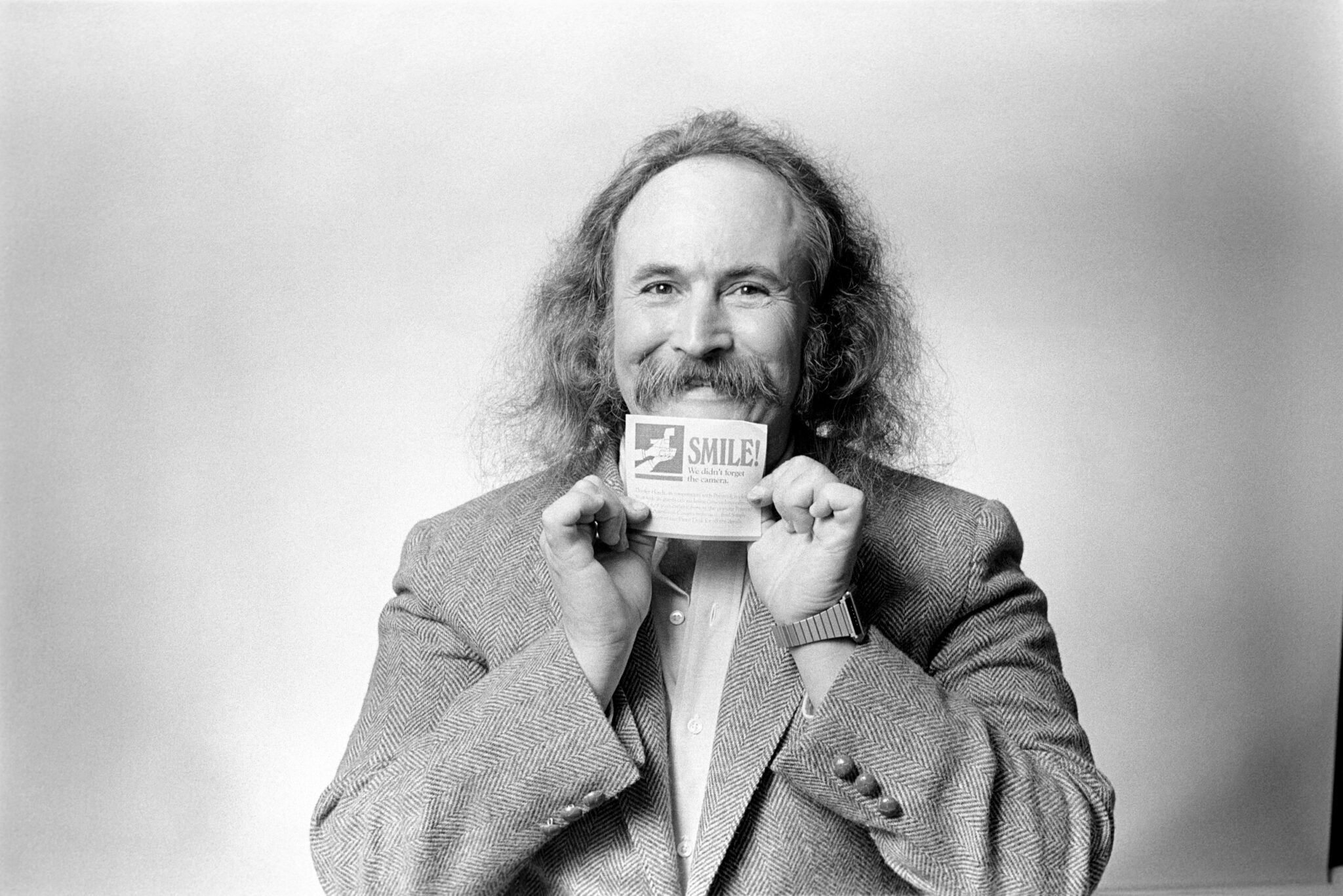

Barely able to keep his eyes open, David tells Hunter, “I’m a happy man, I’m a very happy man. If I was put here on this planet to do anything, it was this [singing]. I’m just happier than I could possibly be, man. Things are looking great. You saw what we do, you saw how well we’re doing, you see my friends are still my loyal friends. I’m just overjoyed to be back doing exactly what I’m supposed to be doing. I’m a very happy man.”

After the interview, I approach David and ask about his health. He stares vacantly at me for a moment, then coos, “I’m doing great, I’m very happy. I’m back playing and singing.” Before I can ask anything else, he looks at his bodyguards and blurts, “I gotta go inside for a minute” and again disappears into his van. I’m left alone with Casanova. I ask to interview him, and he snaps, “Take your best shot; we’ll take ours later.”

While Casanova speaks ebulliently of the future, David peeks through the blinds of his van. Here he is, at the rock reunion of the ’80s, and he is forced to watch from afar. I wonder why. Are his handlers afraid of something?

Indeed they are. Before a planned CSN reunion with Neil Young, the trio is moved into another van, and it’s then that I learn about the management’s fears. Live Aid staffers are specifically instructed to barricade a side entrance to the van. David’s new quarters are off limits, I am told, to insure that no one passes him any drugs. Similar precautions are outlined in the tour’s insurance policy, including a prohibition against David’s driving. Casanova has also imposed another restriction: Jan Dance, nicknamed “Spot” (as in “See Spot run”), is banned from the tour. She has also been barred from joining him at Live Aid. Casanova believes the middle-aged, sandy-haired woman is a “detriment to David’s life.” She was arrested last year in Kansas City aboard an airplane for possessing a gun and drugs. Casanova blames Dance for David’s drug problems. “She might’ve burned at Salem at one time,” Casanova says.

“The lady is very unhealthy, both physically and mentally,” says Casanova. “David feels guilty about her, because the lady previous to her died, and he felt responsible. He has a big guilt complex. If she was out of his life, I think David would have an 80 percent better chance. She’s living in his house. You can’t get rid of her. She’s got her hooks into him so badly. He knows it, he just can’t do anything about it. She’s not on the tour because of me. That’s one of the guarantees I gave Graham.

“No one can tell him what to do. They can’t say, ‘Well, you can’t bring your old lady . . .’ Because he’ll just say, ‘The hell with you.’ David is stubborn enough that if you push him in the wrong direction, he’ll do that. I told him, ‘I’m not going to threaten you, but it’s a very crucial time to be going on tour with Stills and Nash. This is a turning point.’ He was very broke. So I just said, ‘It’s up to you. But if you want me on the tour, Jan doesn’t go.’

“He was upset. He didn’t want to tell her. He felt guilty; fear enters into it, too. She has an influence over him that’s uncanny. There’s a lot of psychic phenomena that goes on. If David knew I was saying his old lady was into black magic, he’d be very upset.

“David calls her, but every time he talks to her she brings him down, because it’s always ‘I need, I want, you promised . . .’ As soon as she finds him, she’ll call four or five times a day. A lot of times I ward off the call, a lot of times he takes the call. He calls her a couple times a week. Then he starts feeling guilty about what’s going on back there.”

“She’s an outgrowth of his problem,” says David Vogelstein, David’s lawyer. “Anyone who abuses drugs surrounds himself with people who are abusing. She’s not helping him, but if David is abusing drugs, it’s his problem. You can’t blame her.”

I want David to settle this debate, but he remains secluded.

Neil Young appears onstage at Live Aid, and in that raspy, growling, pained voice begins to sing, “The Needle and the Damage Done”:

I sing this song because I love the man

I know that some of you won’t understand

Oh—the damage done

I’ve seen the needle and the damage done

I watched the needle take another man

A little part of it in every man

Gone, gone, the damage done

And every junkie’s like the setting sun.

David finally emerges for the CSN&Y reunion. Flanked by his bodyguards, he moves mechanically ahead, ignoring me and all my questions.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post Neil Young on David Crosby: ‘I Remember The Best Times’ appeared first on SPIN.